Antarctic Life Transmissions

Glove, sweet glove

When people find out that I work in Antarctica, one of the first questions they usually ask is how I manage to stay warm while living and working outside in such cold temperatures. With the many layers of wool, down and synthetic clothing we wear, it is actually fairly easy to keep warm in even the coldest and windiest of conditions, with the exception of our hands. They are certainly the most common victims of frostbite, and while many people who work in Antarctica can rely on thick gloves or mittens to protect their hands from the cold, the delicate and often fiddly nature of conservation work means that bulky, awkward gloves aren’t often an option for us. As such, cold hands are just an accepted part of our everyday reality, but that certainly doesn’t stop us from trying to come up with the best possible glove/mitten solution for whatever type of work we are doing at the moment. Just as chefs have their various knives and golfers their different clubs, Antarctic conservators each have a complete stable of glove options for their various tasks, and here’s what I tend to rely on:

For general use, I wear two pairs of fleece mittens handmade by a friend in Banff. Though they are a warm and comfy option, I must admit that they aren’t overly windproof and don’t have any good grip, so aren’t really great to wear for carrying things. Also, should I need to do anything that requires the dexterous use of fingers, such as writing, changing camera lenses, or most conservation tasks, I need to take them off thereby putting my hands them at the mercy of the elements. The solution to this problem is simply to wear a thin pair of fleece gloves underneath my mitts if I know I’m going to be tackling tasks that I need my fingers for. I also have a pair of mitts that have tips that fold back to expose fingerless gloves underneath – the best of both worlds, really. For heavy lifting or snow shovelling, there’s nothing more practical than insulated leather work gloves, and for extremely cold tasks like riding skidoos, we rely on heavy duty windproof mitts with double fleece liners.

Whenever we handle artifacts or use solvents of any kind we must wear nitrile gloves; luckily we can fit a thin pair of polypropylene glove liners underneath them. This combo is still the coldest of all, so we often shove a handwarmer (like the ones you might use on the ski hill) inside each of our gloves, though this still only gives us about fifteen minutes of working time before the whole lot has to get stuffed inside other mittens to warm up again. We have even more gloves that we use for especially dirty tasks like archaeological excavation or refuelling of generators – I prefer to use insulated gardening-type gloves,. And sometimes, there’s simply no glove that will do the trick and you must simply endure the cold with your bare fingers for as long as possible.

And finally, aside from my everyday mitts, my favourite gloves have to be the fleece ones that I’ve modified by adding a grippy panel to one finger, which lets me easily turn the pages of my book while lying in my sleeping bag at night without getting cold hands!

- work gloves for grippy tasks

- waterproof gloves for excavation

- sometimes only bare hands will do

- polypropylene gloves fit underneath nitrile gloves!

- it’s pretty much impossible to wield a scalpel wearing gloves

- conservation wearing my favourite mitts

- a bit of both

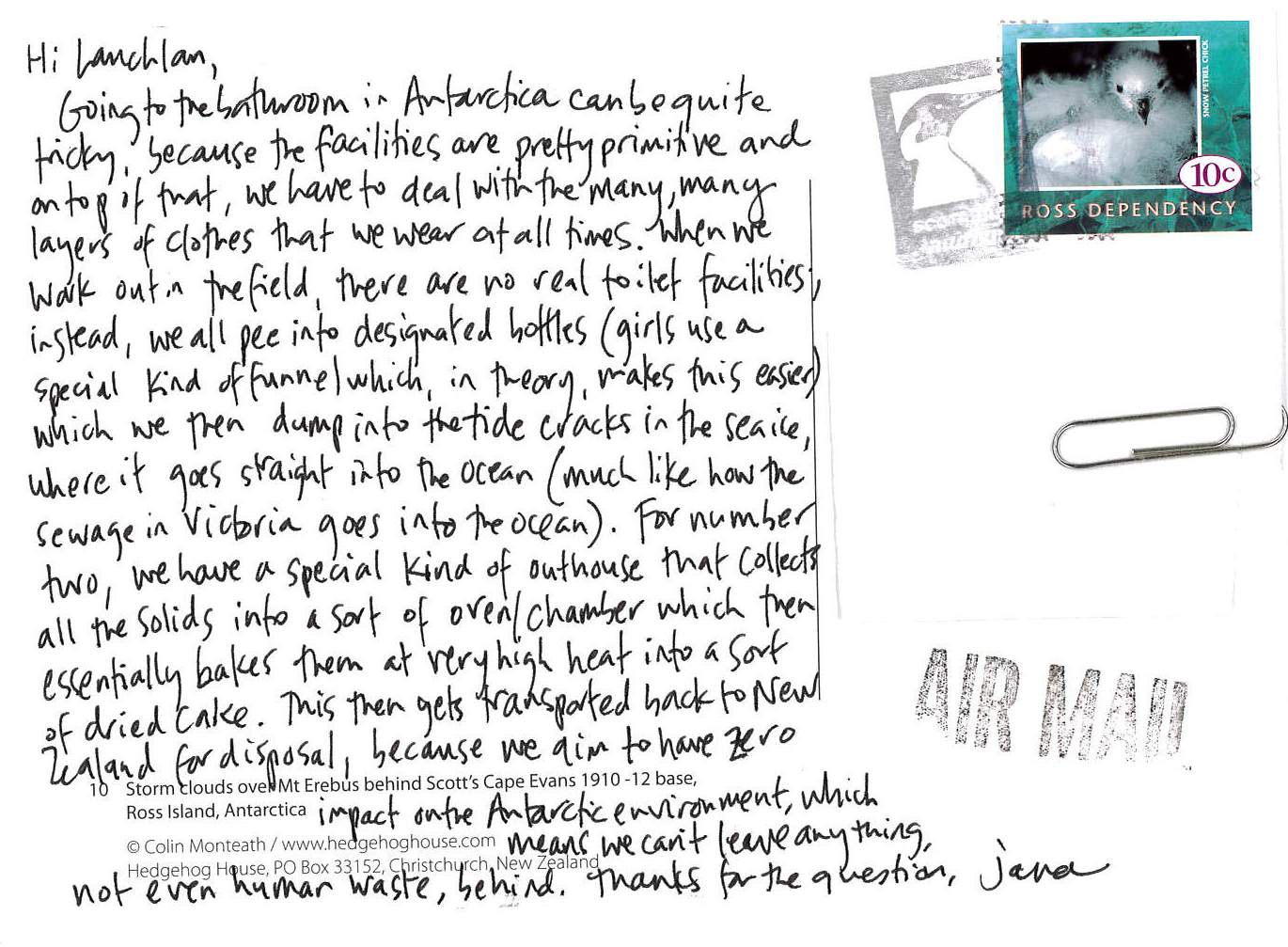

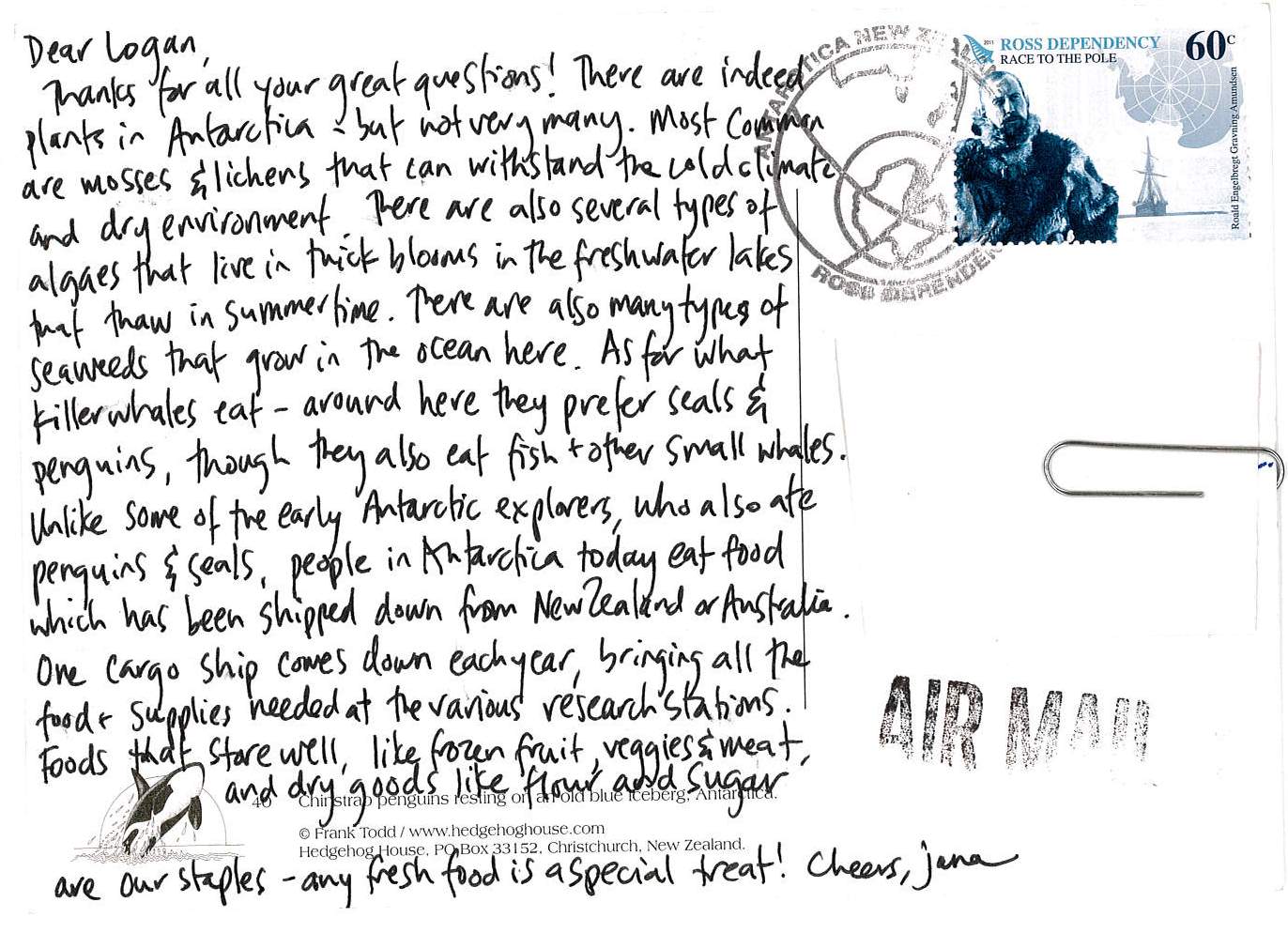

“How do you get food? Are there any plants? What do killer whale eat?”

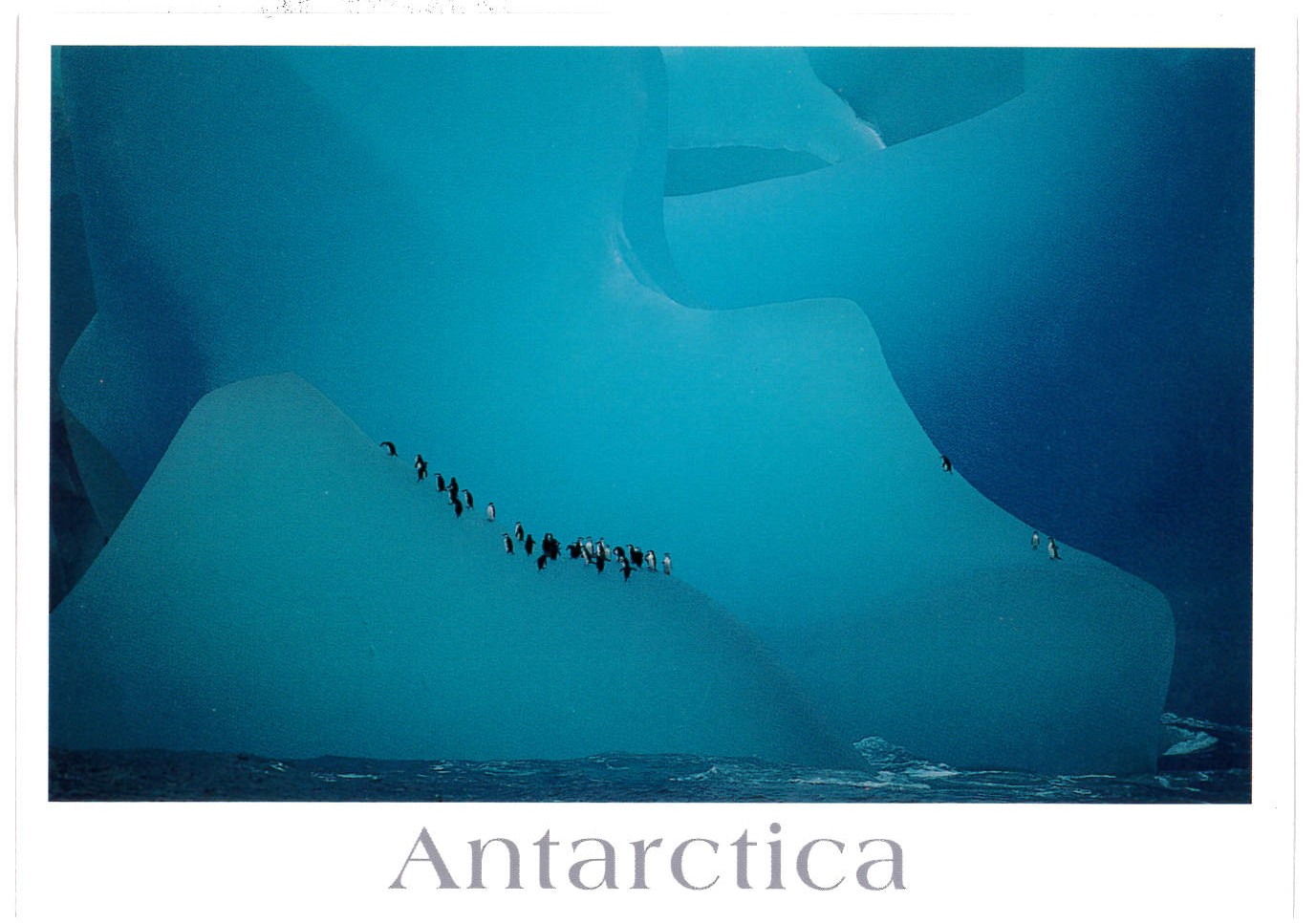

postcard & image ©Frank Todd www.hedghoghouse.com

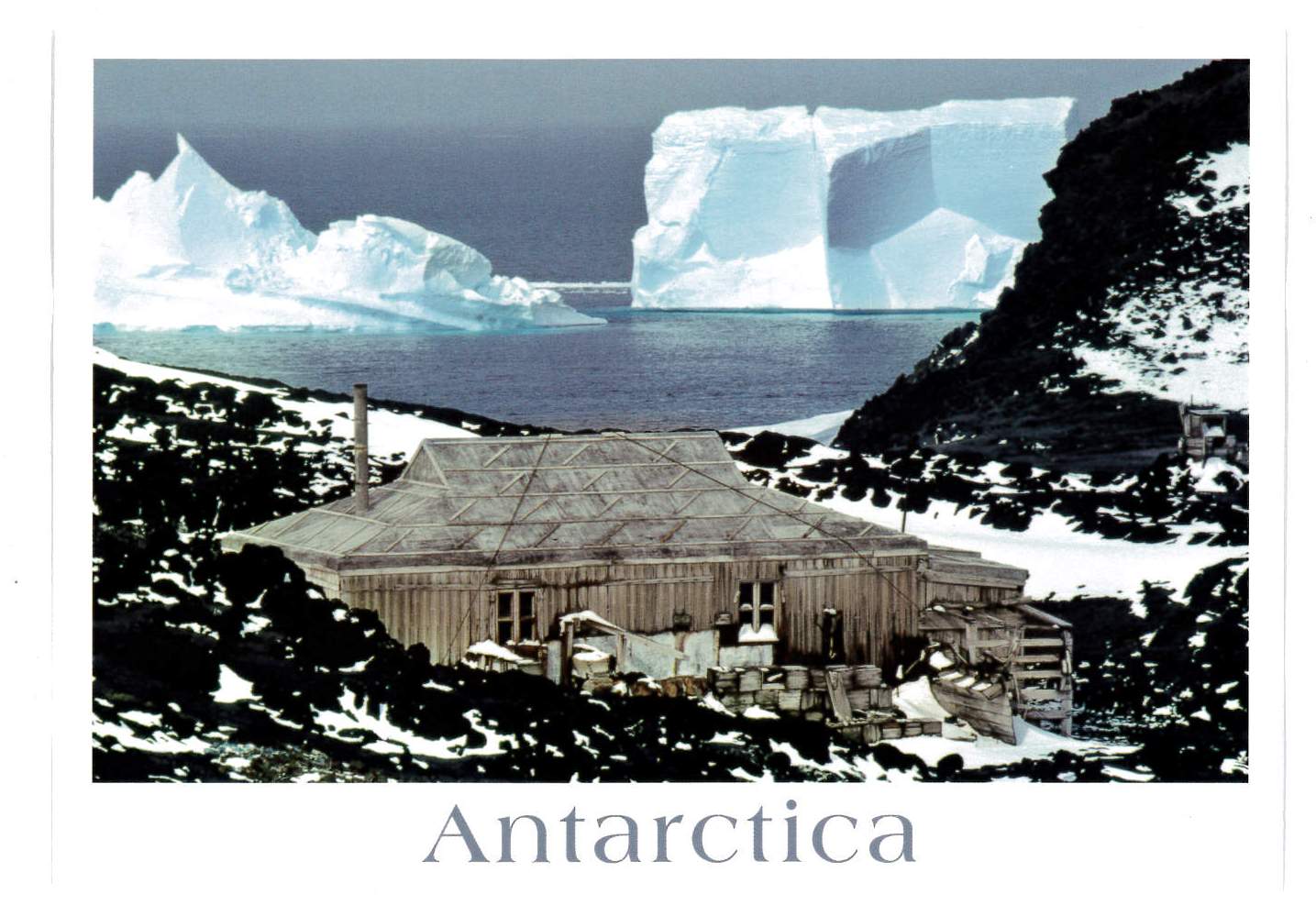

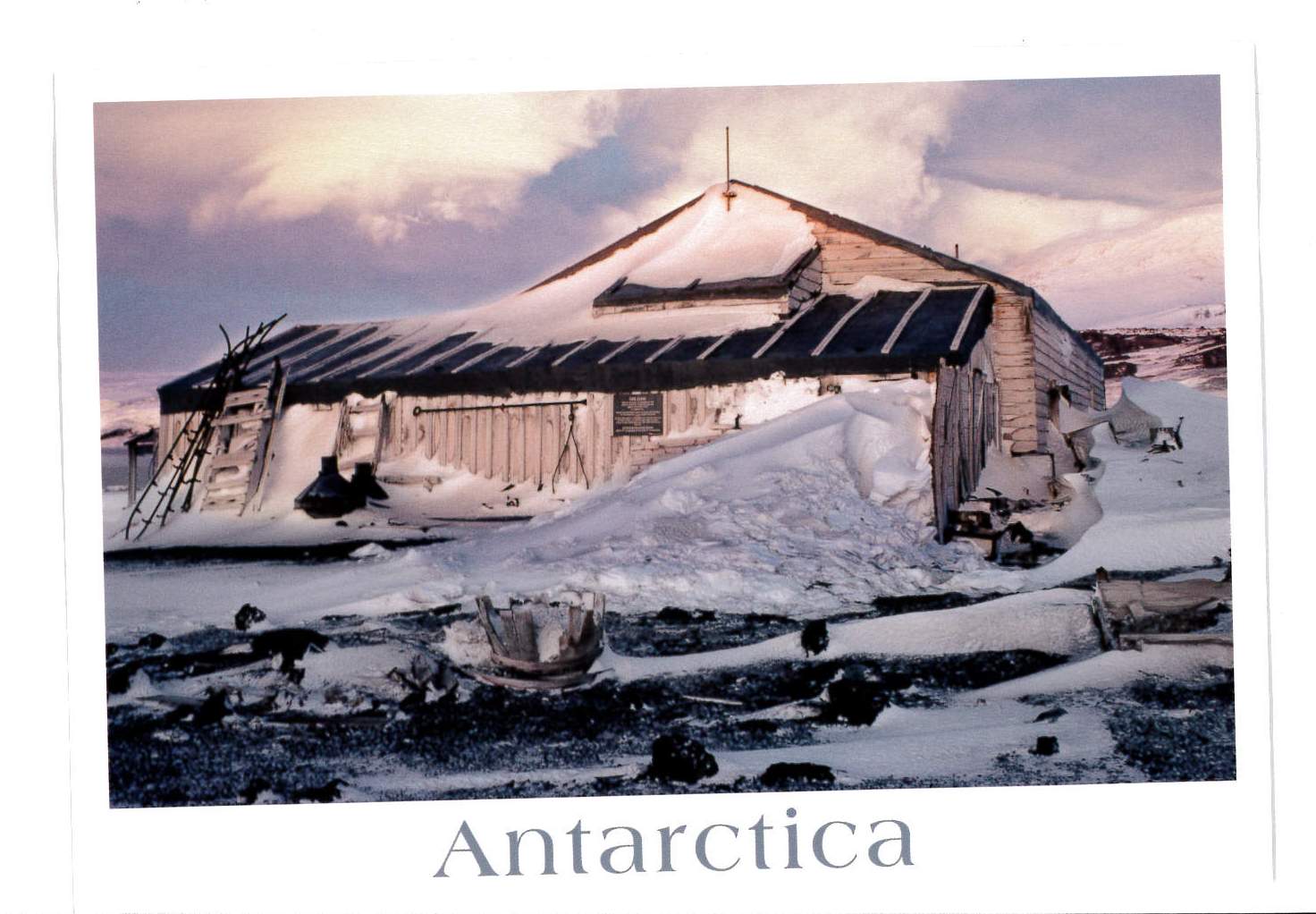

An Ocean of Ice

Because the only way for the early explorers to approach the Antarctic continent was by ship, all of the historic sites that we work on are situated on the coast. And because the landscape surrounding these sites consists mostly of extremely rough and rocky volcanic cliffs, the easiest way to travel around Ross Island is on the sea ice. All of Antarctica is surrounded for most of the year by a wide belt of pack ice that forms, grows and shrinks depending on the season. When this ice is thick enough (usually in late winter, spring and early summer) we are able to walk, drive and even camp on it, but it takes a little bit of work to make sure that it is safe to do so. We have special drills and measuring tapes that we use to figure out if the ice is thick enough to travel on, and we are constantly monitoring the sometimes sizeable cracks that form in it to ensure that they are safe to cross. We establish routes that are known to be safe to travel on, and mark out designated ice ‘roads’.

Where the ice crashes into the shoreline, numerous tide cracks form, and we have to be especially careful when moving across these as they can change significantly throughout the course of even a single day, and a wrong step can result in an accidental swim! Because the sea ice is really just the ocean in frozen form, it too is affected by the tides and currents, and often gets pushed towards the shoreline in bays, coves and other restricted areas. In these areas, the pressure of the ice being pushed against the static shoreline forces it to crest up into fantastic formations called pressure ridges. The ridges get more and more pronounced as the ice gets pushed shorewards, and you can often hear the creaking and groaning of the ice getting forced upwards. We often go for walks between the ridges in the evenings when the sunlight is low and shining brilliantly off the ridges, and they are without a doubt one of my favourite things about living in Antarctica.

The warm summer weather causes the pressure ridges as well as the rest of the sea ice to weaken considerably, and all of the ice eventually breaks out leaving only open water where once there seemed to be solid ground. At that point we can travel only on the ‘hard’ (as the land around here is called), or by helicopter. The open water can sometimes last for months, but at times it may only be a couple of hours before new ice forms and the pack moves back in for the following year! It is never dull living in such close proximity to such a dynamic surface, and the sea ice never ceases to amaze me!

all photos and text: Jana Stefan 2013

- pressure ridges at cape armitage

- pressure ridge

- our old campsite is now underwater!

- new pancake ice forming even as old ice is still breaking out

- measuring sea ice thickness at a tide crack

- hagglunds travelling on ice road in front of mount erebus